Description

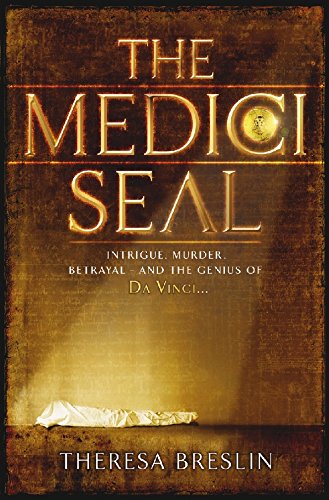

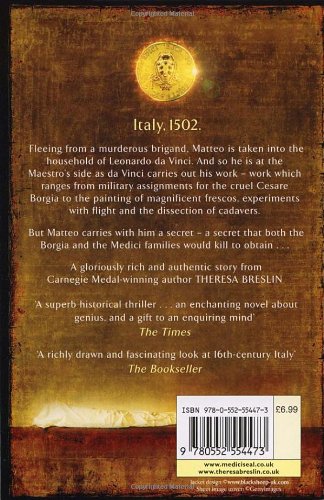

The place is Romagna, Italy 1502. Fleeing from the murderous brigand Sandino, Matteo – a young boy – is saved from drowning by the companions of Leonardo Da Vinci. From this moment on, Matteo is at the Maestro’s side as he carries out his work, which ranges from the painting of magnificent frescos to intricate dissection of the human body.

But Leonardo is employed by Cesare Borgia, head of one of Italy’s leading families. Cruel and ruthless, the Borgia punishes without mercy those who oppose him or who threaten him in any way. And as Da Vinci and Matteo travel across Italy on the Borgia’s business, murder, deceit and revenge follow in their trail. For Matteo carries with him a secret – a secret that both the Borgia and Medici families would kill to obtain.

A gloriously rich and authentic story of the Renaissance, “The Medici Seal” is also both the personal story of Matteo, a boy becoming a man, and a fascinating glimpse into the world of Da Vinci.

Shortlisted for the Royal Mail Scottish Children’s Book Awards 2007